Glaucoma

Most of what I see and treat is glaucoma.

What is Glaucoma?

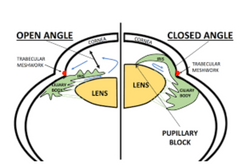

Glaucoma is a process whereby the optic nerve is (usually) slowly and with no symptoms destroyed due to the pressure of the fluid inside the eye (called the intra-ocular pressure or IOP) being too high for that particular eye. Let’s describe the normal workings inside the eye so that we can understand what goes wrong in glaucoma. There is a fluid produced inside the eye (called the aqueous) that is produced behind the colored part of the eye (the iris). This fluid flows through the pupil (which is just a hole in the iris. This hole allows light to get to the retina so that we can see) and drains out of the eye in the angle between the outside edge of the iris and the base of the cornea, right where the iris meets the white part of the eye, the sclera. This angle is known as the drainage angle. This angle contains the drainage trabecular meshwork which is responsible for draining the aqueous out of the eye and into our blood stream from whence it was produced.

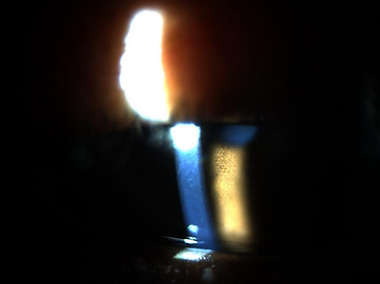

The aqueous fluid has to exit through the trabecular meshwork to keep the fluid from backing up into the eye. This is where the problem is. Something prevents the fluid from exiting through the trabecular meshwork, be it the functioning of the meshwork itself (primary glaucoma) or something else (secondary glaucoma). Ophthalmologists look at this drainage angle with a big contact lens called a Gonioscopy lens.

There are two types of glaucoma, open angle and closed angle. Each can be primary or secondary. Secondary means caused by an identifiable reason. If the drainage angle is not obstructed by the iris, this is called an open angle. (Despite being called “open”, the aqueous cannot exit the eye through the drainage meshwork). Open angle glaucoma is by far the most common type of glaucoma in the U.S.A. (Closed angle glaucoma is the most common type in Asia). If there is an identifiable cause of open angle glaucoma, this is called secondary open angle glaucoma or SOAG. If there is no identifiable cause aside from the trabecular meshwork being abnormal, then is called primary open angle glaucoma or POAG. In general, primary means no identifiable cause for a disease. Later on, I’d like to discuss one SOAG in particular, Pigmentary Dispersion Syndrome (PDS).

We believe an abnormal protein in this meshwork is responsible for the decreased draining ability of the eye and the subsequent higher intraocular pressure inside the eye. This higher IOP pushes on and slowly kills the optic nerve. This process of killing the optic nerve is called glaucoma. We will only discuss adult-onset glaucoma and leave congenital glaucoma for pediatric ophthalmologists to discuss. Shown below are two diagrams showing a normal angle. The risk factors and the two types of adult glaucoma, open angle and closed angle, are described below.

What are the Risk Factors for open angle glaucoma?

The major risk factors are:

-

Age 60 or higherFamily history of glaucoma

-

Corrected/uncorrected intraocular pressure of 21 or higher.

-

Increased cup to disk ratio 0.5 or higher (this ratio is defined under "how do we detect glaucoma")

-

Disk hemorrhage found on exam

-

Nerve fiber layer defects found on exam

Minor risk factors include:

-

Race. 1 in 10 African Americans above age 80 have glaucoma as compared to 1 in 50 Caucasian Americans. This has led to the idea that being African American is a major risk factor. Recent evidence, however, points towards thinner corneas in African Americans as being one possible explanation for this higher rate.

-

IOP changes inside an eye of 6 or greater

There are a number of other minor risk factors for open angle glaucoma mentioned in other studies, but none that have been shown to be consistently significant. The more risk factors you have, the higher your risk for developing glaucoma.

What are the risk factors for closed angle glaucoma?

-

Hyperopia with Age 50 or higher

-

Asian descent

-

Some rare other types such as aqueous misdirection and lens subluxation

7 photos showing an open angle and a closed angle with the iris pushed into the trabecular meshwork:

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

|

Pressure from the flow of the aqueous trying to get through the pupil pushes the iris forward towards the trabecular meshwork. This is called iris bombe. Iris bombe can sometimes cause the iris to bow forward too much and into the trabecular meshwork, resulting in its complete blockage. Complete blockage results in primary angle closure glaucoma and this can raise the IOP to 60 mm or even higher.

Pressures this high can cause blindness in a few days and constitute a medical emergency. The treatment and cure for this is placing a small hole in the iris with a laser (called a laser peripheral iridectomy or LPI, done easily today with in-office lasers), which allows the aqueous to vent through the iris, equalizing the IOP on either side of the iris, and avoiding the blockage of the iris at the pupil/lens area. Once the hole is formed, the iris falls back towards the lens and away from the drainage angle.

|  |  |

|---|

This opens the drainage angle up and allows the aqueous to drain normally again. An LPI is actually a permanent cure for angle closure glaucoma. Cures in medicine are not that common so this is a really great procedure to have in our arsenal!

We screen patients for narrow angles during a routine eye exam with the slit lamp. Optometrists refer patients to an ophthalmologist if the angles look narrow. If an angle is too narrow and in danger of closure, we perform an LPI prophylactically, before a closed angle attack occurs. Some people do not know that they have narrow angles and present to the ER in full blown angle closure glaucoma. People who are far-sighted, of Asian descent and/or over 50 years of age are at higher risk of developing angle closure glaucoma and should have gonioscopy done by an ophthalmologist to make sure that they don’t have narrow angles. For some reasons, most angle closure attacks occur when someone is walking from a dark room towards light (and seems to happen at 9:00 PM on the weekend when an ophthalmologist is not readily available).

Some over-the-counter medications will state that if you have glaucoma or are a glaucoma suspect, don’t take the product without checking with your ophthalmologist. What those medications might do is to dilate the iris and in those patients that have iris bombe, precipitate an angle closure attack. This is rare and if your ophthalmologist determines that your angles are open on gonioscopy, there is no need to fear taking medications that have this statement. Medical steroids (catabolic steroids, not sports or anabolic steroids) can cause very high pressures with open angles in some patents but this is a well-known side effect of these medications (prednisone is an example) and you should be screened for this by your ophthalmologist within 10 days of starting these steroids.

So, now that we have covered the two types of glaucoma, open and closed, let’s talk about how we detect glaucoma.

How do we detect glaucoma?

Risk factors for glaucoma or findings on the eye exam can raise the question of glaucoma during a routine eye exam. Most referrals to ophthalmologists for suspicion of glaucoma are due to a high IOP reading on the air puff test or an enlarged cup to disk ratio seen by an optometrist during a routine eye exam. If you have a corrected IOP (corrected by your corneal thickness, which is explained below under tonometry) of 30 or higher, you probably have glaucoma. If you do not have glaucoma outright, you are called a glaucoma suspect. You may be a suspect for many years, but being a glaucoma suspect is better than having glaucoma. Ophthalmologists and Optometrists look at the following items in order to classify a patient as having glaucoma or as being a glaucoma suspect.

Tonometry: This is a fancy term describing the measurement of the intra-ocular pressure (IOP). Most Optometrists use the air puff method, which is not as accurate as the blue light method (Goldmann) that most ophthalmologists use. Of all of the risk factors mentioned above, the only one that we can alter and therefore treat open angle glaucoma with is by lowering the IOP. A very important study (the ocular hypertensive treatment Study or OHTS) conclusively showed that a thicker or thinner cornea will throw off our tonometer’s calibration and hence our reading of the true IOP. Thicker corneas give a falsely high number (someone may measure 24 on the test but really have an IOP of 18) and thinner corneas give a falsely low IOP measurement (someone may measure 19 on the test but really have an IOP of 26).

A pachymeter measures the thickness of the cornea. The IOP result after taking the corneal thickness into account is called the “corrected IOP”. Ophthalmologists are still grappling with integrating the OHTS into everyday practice. Full integration will require challenging long-held beliefs by many academic ophthalmologists that need to be modified in light of this new study. I believe that you do not know what the true IOP is until you have performed pachymetry.

Cup to Disk ratio (C/D):

The optic nerve starts in the retina and goes to the brain. The optic cup is a light depression in the surface of the optic nerve without any optic nerve fibers in it. The size of the cup compared to the size of the disk is called the C/D ratio. The higher the ratio, the higher the risk of developing and treating glaucoma. The cup cannot be physically bigger than the disk. Over time, glaucoma destroys nerve fibers and this causes the C/D ratio to enlarge so we take photos of the disk every year and compare the recent one to the first one to see if the C/D ratio is changing. A rare sign but very significant if it is present. A large cup is sign that there might be fewer nerve fibers in the optic nerve.

The first two photos below show a normal sized cup in someone with diabetic retinopathy. The two photos below those show an enlarged C/D ratio. Most people are born with small to medium sized cups but some patients are born with a large cup, so having a large cup does not necessarily mean that you have glaucoma.

Below are 4 photos of enlarged cups. The last photo on the right also has geographic atrophy.

Therefore, a large cup is a risk factor for developing glaucoma and may be a sign of having glaucoma. When a patient has glaucoma, this destruction can get severe enough that some areas of the retina no longer send light impulses to the brain and that area of the retina goes blind. Think of a large cable with many small wires in it. If you snip enough of the small wires, you will eventually loose most if not all of the transmission capability along that cable. The eye works in the same manner. When we see a patient with a large cup, we need to differentiate a normal large cup from an early glaucomatous cup. We do this is by following the patient over time, looking for the cup to enlarge or stay the same size. Changes in the cup can take months or years to become noticeable. Even if the cup stays the same size, you are still at risk for developing glaucoma. If the cup enlarges, then you do have glaucoma. Taking digital photos of your optic nerve once a year and then comparing the two photos side by side is the best way to detect changes in the C/D ratio. I do this on all of my glaucoma and glaucoma suspect patients.

How do we work up glaucoma patients?

We do the following;

Gonioscopy: This has to be done in order to determine whether the angles are open (no iris tissue up against the drainage angle) or closed and you are in danger of developing angle closure glaucoma. Gonioscopy is recommended once every 5 years.

Visual Field: This has been our gold standard for detecting glaucoma for 100 years. 40% of your nerve will be dead before the defect shows up on the visual filed test and this is our best test! When glaucoma starts to damage the optic nerve, it will not affect your straight-ahead vision nor your side vision way out to the side. It will initially decrease your peripheral vision just above and below your straight-ahead gaze. Imagine that you are looking at the center of a door. Initially, glaucoma will decrease your ability to see the top and bottom of the door as you look at the center of the door. At first, the decrease will be very subtle and you will not notice it. As glaucoma progresses, the peripheral field loss can become very noticeable. By the time you notice a visual field defect, 90% of the nerve is dead and the damage is permanent. We cannot get it back. This makes early detection and treatment very important.

In the visual field machine, we cover one eye and line up the other eye for testing. What is important is that you keep looking straight ahead at the fixation light the whole time so that we can test your peripheral vision. The first thing that the machine finds is your natural blind spot. We all naturally have a small blind spot in each eye that is formed from a lack of retinal tissue over the optic nerve. (The retina converts light into electrical impulses that go to the brain so that we can see. No retina, no vision). The machine uses the blind spot to detect when you are not looking straight ahead during the test. Increased fixation losses reduce the reliability of the test. There can be sometime between when lights are presented to you during the test and this makes some patients nervous. They think that they should be seeing lights all of the time so they start looking around for them. The machine detects this as a fixation loss and this reduces the reliability of the test. Don’t worry if you don’t see a light for a while, you aren’t supposed to see 40% of the lights anyway! Defects in the visual field show up as dark spots on the printout. Newer VF machines use a virtual reality head mask to perform the test and I have been impressed with how well they function.

Tonometry: Discussed above.

How do we treat Glaucoma?

Laser treatment (SLT): In patients that have POAG or are at higher risk of developing POAG, for initial treatment, I strongly recommend an in-office laser treatment that takes 20 seconds to perform called Selective Laser Retinopexy (SLT). (Don’t confuse SLT with the older laser ALT in your google searches.) SLT places small holes in the drainage trabecular meshwork so that the aqueous can drain out of the eye better. It has been shown in a major clinical trial to be as effective as drops in the initial treatment of glaucoma. If it does not work, drops are as effective after SLT as before SLT, so we have little to lose in trying SLT first.

The success of SLT seems to be related to how much pigment is in the drainage meshwork, the more pigment, the better SLT works. Overall, 90% of patients will respond to SLT by lowering the IOP. The effect of SLT slowly wears off but lasts for an average of three years. SLT does reduce the need for drops during those three years and, for many patients, makes non-compliance less of an issue. I have had some patients that presented IOP’s above 40 that had their IOP go down to 15 within a week after SLT. This is an exceptional response and is not typical, however.

As you can tell, I am a fan of SLT!

Drops: If SLT is not enough to control the glaucoma, we resort to the use of glaucoma drops. Today, we have very effective drops that are easy to take. Compliance with taking the drops is directly related to how many times a day they need to be administered. The more drops you need to take every day, the less likely you are to take them. Fortunately, new drops have been developed that lower IOP significantly and have once-a-day doses. Multiple types of drops may be needed in order to get your IOP to a safe level.

Minimally Invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) procedures during cataract surgery: I think that this is a good option for patients with glaucoma and cataracts and should be discussed with your cataract surgeon prior to cataract surgery. Complications are less than with trabeculectomy/ Tube surgery and it is easy to do during cataract surgery. I have not been impressed with the results of MIGS.

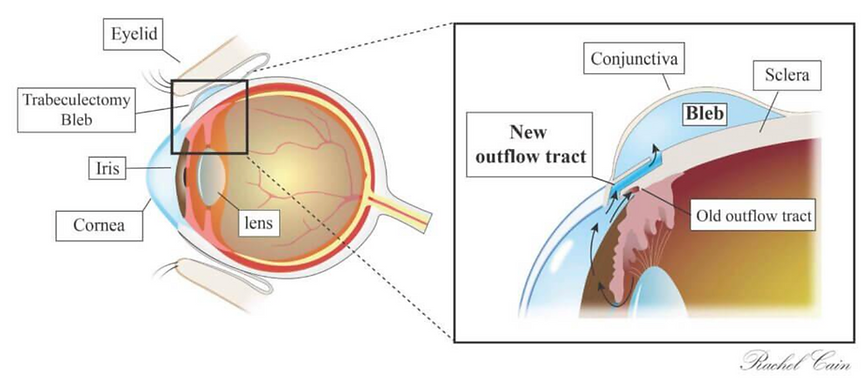

Surgery (trabeculectomy/ Tubes): These are major surgery procedures for the eyes and place a permanent hole in the eye itself. In this country, trabeculectomy/ Tubes surgery is the option of last resort due to these complications. Socialized medicine countries who don’t want to pay for drops and use these surgeries as a first line of treatment. Complications are high, especially compared to the above three options, and can include a permanent worsening of your vision. But, if SLT and drops are not doing the job, we have to do a trab or a tube.

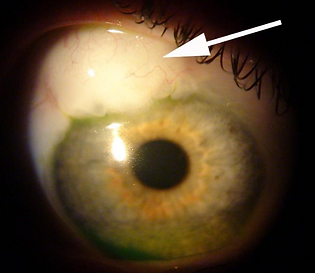

Arrow pointing to the bleb created by a trab surgery. A raised bleb is a sign of a functioning bleb.

Pigmentary Dispersion Syndrome (PDS):

This is a type of SOAG. This is described in the academic literature as a “rare” type of secondary open angle glaucoma and it has caused some controversy in the academic ophthalmology circles. The best theory, in my opinion, as to how it occurs is as follows. Due to a higher aqueous pressure in front of the iris than behind it, the iris bows backwards towards the lens. Our best guess as to why this pressure differential occurs is that blood pressure pulses from the retinal arterioles sets up pressure waves that get transmitted through the pupil, reflected off of the cornea and push the iris backwards. In any case, this backwards configuration, easily seen on gonioscopy, sets up the problem. Every time the iris dilates and constricts, pigment from the back of the iris is rubbed off by the “ligaments” (called zonules) that hold the lens in place.

These pigment particles float free in the aqueous and are deposited on the back surface of the cornea where it forms pigmented lines known as Krukenberg’s spindles shown here

The pigment also gets deposited in the drainage meshwork, plugging it up. If enough pigment gets rubbed off, transillumination defects occur in the iris which are seen as radial lines in the iris by your doctor and shown here

Most optometry referrals for PDS to Ophthalmologists are due an excellent Optometrist noticing Krukenberg’s spindles or iris transillumination defects during a routine eye exam. Photo showing 4+ pigment in the drainage trabecular meshwork

Initial treatment of PDS includes SLT which works very well in PDS due to the high amount of pigment in the drainage angle. One more word about PDS. The academic literature is full of descriptions of PDS that I have not found to be reflective of my private practice. PDS is described as a rare entity that confers a 50% chance of developing glaucoma. I have had about 50 cases of PDS in my clinic alone in the last 5 years and I find that less than 10% of these patients develop damage of the optic nerve. (And, I see patients with PDS at all ages). I have checked many of my patients after exercise and

I have not seen the high IOP spike that may occur after exercise. I don’t want you to get discouraged if you read other sources of information on PDS. Why the difference in my experience and the academic literature? Well, technology has changed. In office LPI’s were not available before 1990 and LPI's had to performed with surgery in an operating room. Also, academic centers tend to get the more severe cases referred to them from private practice and, since academic centers write most of the research on a subject, they can make a condition more dramatic than it really is. I think that this is true for PDS. Recently, the treatment of corneal ulcers was found to be very different at academic centers than in the private practice world due to some of these same reasons.

This web site has taken most of its information from the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Preferred Practice Patterns publications. Each person’s medical condition is unique and all information should be reviewed with their ophthalmologist before deciding on any course of action. We cannot be held responsible for any use, misuse or outcomes from the information contained herein. Thank you.